Children's rights in India Despite

Constitutional guarantees of opportunity and civil rights, millions of children

face wide-spread deprivation and discrimination. A large part of this stems from

being seen hrough the lens of adults who make decisions for them, and who prefer

to address their welfare rather than their rights, says Enakshi

Ganguly Thukral.

Combat Law, Vol. 3, Issue 1 - Every time my 16-year old daughter gets on to stage to dance, she dusts some extremely fine shiny stuff on her face and it glitters and shines. By the time she is off the stage, most of the shiny glitter is gone, except for some bits of sparkle here and there, and by the next morning there is no trace of it. India's shine is much like that - here today, gone tomorrow - effervescent and transient.

Combat Law, Vol. 3, Issue 1 - Every time my 16-year old daughter gets on to stage to dance, she dusts some extremely fine shiny stuff on her face and it glitters and shines. By the time she is off the stage, most of the shiny glitter is gone, except for some bits of sparkle here and there, and by the next morning there is no trace of it. India's shine is much like that - here today, gone tomorrow - effervescent and transient.

Every day we see articles focusing on the shining and the

non-shining `bits' of India. But if anything or anyone truly shines in India

today, it is her children, comprising over one fourth of our population.

Resilient and lively, they continue to smile and give hope in the not so shining

bits of India that most of them inhabit. But then, they are not voters. What

they think or feel does not count.

Indians constitute 16 per cent of the world's population,

occupying 2.42 percent of its land area. India has more working children than

any other nation, as also among the lowest female-male ratios. Despite

Constitutional guarantees of civil rights, children face discrimination on the

basis of caste, religion, ethnicity and religion. Even the basic need for birth

registration that will assure them a nationality and identity remains

unaddressed, affecting children's rights to basic services.

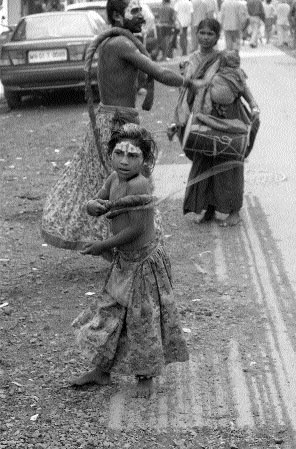

India is also home to one of the largest illiterate citizenries

in the world. In the not so shining India we see, hear and read of, children are

dying of starvation, while food in our granaries rots and feeds rats. We watch

while the female sex ratio dips. Little children, barely able to stand, are

married off flouting all laws. Little ones are sacrificed, trafficked and sold;

as others are locked, abused, sodomised - the list is endless. And there are all

those realities that never make the news. We know this is only the tip of the

iceberg, but we choose not to act. Our silence and tolerance not only condones

such violation of rights, it also makes us guilty of complicity.

Therefore, any understanding of human rights of children cannot

be confined to some children - 'poor children', 'working children' and

'marginalised children'. Such categories only help us to remove ourselves from

the problem. Let us not delude ourselves. Violations of children's rights are

not limited to the poor and downtrodden. They happen in middle class and elite

homes too, albeit in different forms, and the silence around these is even

deeper. Also, any analysis on the situation of children must be understood

within the context of the economic and political changes in the country. Of

particular importance are globalisation and liberalisation, and the gender,

caste and religious attitudes that prevail today. All these add to children's

vulnerability and affect any action that may be taken for them.

|

Children are not a homogeneous category. Like adults, they are

divided into different categories based on social and economic status, physical

and mental ability, geographical location etc. These differences determine the

difference in the degree of their vulnerability. While gender discrimination

exists almost all over the world, it is much greater in some countries - and

India is definitely one of them. Girls in vulnerable situations such as poverty,

disability, homelessness etc. find themselves doubly disadvantaged, by their

gender and the physical, economic, political, social situation that they find

themselves in. It is therefore imperative to take a gender perspective into

account in examining the situation of children.

The Rights vs. Welfarist approach

The Constitution of India provides a comprehensive

understanding of child rights. A fairly comprehensive legal regime exists for

their implementation. India is also signatory to several international legal

instruments including the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC). However,

the government seems to be more comfortable with the idea of well-being rather

than rights (with its political overtones). Child rights activists are faced

with challenges of promoting and protecting rights as a positive social value.

Needless to say, ours is not the only government to do so. The

Union Government's ideology resonates with the watering down of the rights based

framework in the recent UN Special Session on Children which failed to reaffirm

international pledges made in 1990 to protect the rights of children.

The government's approach remains largely welfarist. India is

yet to adopt a single comprehensive code that addresses the provisions of the

CRC. Clearly the draft National Policy (Charter) for Children which has been

recently passed in parliament, and is envisaged as being such a code, is

inadequate as it does not address the full range of rights. It does not make any

reference to the CRC. In the words of the Joint Secretary Department of Women

and Child, GOI, it captures the 'essence of the CRC' thereby does not need to

refer to it!

Child Rights - From an adult's perspective

An examination of the laws shows that although they are meant

to protect the interests of children, they have been formulated from the point

of view of adults and not children. They are neither child-centred, nor child

friendly, nor do they always resonate with the CRC.

The problem begins with the very definition of 'child' within

the Indian legal and policy framework. The CRC defines children as persons below

the age of 18 years, however different laws stipulate different cut-off ages to

define a child. Only the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act 2000 is in

consonance with the Convention. In the absence of a clear definition of a child,

it is left to various laws and interpretations.

|

Access to health - A chimera

The health of our children continues to be a matter of grave

concern, especially in the wake of growing privatisation of health services, and

their increasing inaccessibility for the poor. This is a particularly serious

situation as environmental degradation and pollution lead to a further

deterioration in children's health. The working conditions that many children

are forced to suffer worsens matters.

In our shining India, children suffer from malnutrition or die

of starvation and preventable diseases. According to UNAIDS there are 170,000

children infected by HIV/AIDS in India. Children affected by the virus-whether

children of victims or those who are infected themselves-- live on the fringes

of society, ostracised by people they call their own, unloved and uncared for,

even as our government continues to squabble over numbers of affected people.

Even juvenile diabetes is reported to be taking on pandemic proportions.

While the Constitution lays down the duties of the State with

respect to health care, there is no law addressing the issue of public health.

Children's health care needs continue to be in great part dealt under the

Reproductive and Child Health Programme of the Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, with a focus on reproductive health and safe motherhood and child

survival. The other health needs of children are addressed by the country's

primary health care system; with very little attempt to address these needs

specifically or separately.

The population policy with its coercive manifestations in the

states has of course proved most 'children unfriendly'. Parents aspiring to

political positions are now forced to choose between children and politics. Law

does not allow persons with more than two children to hold elected positions in

local self governments-and many choose politics as they disown their children or

give them up for 'adoption' in an effort to keep to the 'right' family size.

The Government has announced its National Health Policy 2000.

One cannot but note that children do not find mention as a separate category -

yet another example of the lack of child focus in our planning and

implementation.

Education for all - A promise yet to translate

Education for all is also a promise held out by the state. An

examination of State policies and programmes shows that education is not going

to open the promised gateway to equality. Indeed if anything, it is a promise of

'differential education for all' (read 'some' even here). While some children

continue to have access to mainstream schools or expensive private schools, the

rest must contend with 'non-formal' second grade education provided by untrained

and lowly paid 'para- teachers'. As if that was not enough, the new curriculum

framework has opened up a can of worms on the kind of biased syllabus, with

incorrect or incomplete content, that our children will be subjected to.

The passing of the 93rd Amendment Bill (passed as the 86th

Amendment to the Constitution) making education a fundamental right, should have

been an occasion to rejoice. Instead it has become an issue for another long

struggle because it only reinforces the lack of political will to make education

universal and accessible for all. By leaving out those in the critical 0-6 years

age group, putting the onus of creating conditions on parents for sending

children to school and making it their fundamental duty, by reinforcing parallel

streams of education, the amendment has once again sealed the fate of poor and

marginalised children.

Although the rhetoric speaks of free and compulsory education

for all, in practice, the education system seems to be designed to keep children

out of it. To implement the 86th Amendment, the government has drafted 'The Free

and Compulsory Education Bill, 2003. Concerns and criticisms on this bill are

being expressed by educationists and activists.

|

At a recent workshop attended by children from across the

country was a young spastic child named Debu.

- I have a right to be called by my name. Why is it that all children are called by their names and I am called langda (lame) or even pagal (mad)?

This made all the other children sit up and look at Debu in a

new light. While they had been discussing their rights, it had not occurred to

them that children with disabilities may be denied even this basic right.

Children with disability continue to suffer unequal opportunities for survival

and development. They are denied personal or economic security, health care,

education and all basic needs necessary for their growth. Further certain

disabilities, such as, for example mental disability carry even greater stigma.

And if the disabled child is a girl, then the discrimination is doubled. The

rights of disabled persons has finally been recognised with the enactment of the

Persons With Disabilities (Equal Protection of Rights and Full Participation)

Act, 1995.

Children in situations of crime and exploitation

Recognising the flaws of the 1986 Juvenile Justice Act, the

government passed the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act, 2000. But the

knee jerk reaction in amending the law without a wider discussion and

consultation with child rights practitioners, has left many who are concerned

with children and work with them deeply distressed. In 2003 the government

drafted amendments to the law. But, because of criticisms and concerns raised by

several organisations and groups, it has been placed before a Parliamentary

Standing Committee. The Committee is currently reviewing the law.

Child trafficking is one of the most heinous manifestations of

violence against children. This is taking on alarming proportions - nationally

and internationally. Although, very little reliable data or documentation is

available, meetings and consultations across the country have revealed the

gravity and the extent of this crime. It is high time we understood and realised

that children are trafficked for a number of reasons and this cannot be treated

synonymously with prostitution. The absence of this comprehensive understanding

and a comprehensive law that addresses all forms of trafficking to back it makes

this issue even more critical.

Adoption: The need for greater checks and balances

Adoption is one of the best and appropriate forms of

alternative family care. Indeed, it is the only way to break the mindset of

institutional care for children, which has been posed as the only solution for

many years.

However, adoption of children continues to be determined by

religion of the adoptive parents or the child when religion is known. Only

Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs can adopt children. The personal laws of

other religions - Muslims, Parsis, and Jews do not allow it. Even as it exists

for Hindus, the law has serious flaws discriminating against married women. It

allows only married men to adopt. Further, it only allows for adoption of

children of opposite genders.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act,

2000 also provides for adoption making no exception on the basis of religion. So

more complications may arise. Besides, the large scale setting up of baby shops

and the selling of babies from poor families has caused panic across the

country. We need to be careful not to throw the baby out with the bath water.

Greater checks and balances are required to ensure that adoption is legal and

proper, and that it is not being used as a means of trafficking of children.

Protection from, or by, instruments of violence?

In January 2002, a school going girl in Jammu, while discussing

the Right to Protection said that even in the current environment of unrest she

felt protected because she had armed guards, who accompanied her to school! She

was not alone. There were others too who felt protected because they had guards.

Incidentally, one of them was from the Kaluchak Army School in an army base,

which was attacked by terrorists a month later. We need to ask ourselves what

environment are we providing to our children where they need instruments of

violence to feel protected?

|

Children and disaster mitigation

Thousands of children are homeless or living in inadequate

living conditions. Thousands of others are displaced in the name of development

and progress. Land is acquired for 'public purpose', while the benefits seldom

include those who are evicted and displaced. Yet others are de-housed as a

result of natural calamities - the floods, cyclones, earthquakes that have come

to become almost a regular feature in our country. In all of these, while whole

communities are affected, children are affected even more.

An estimated 3.3 million children were affected by the

supercyclone that hit the coastal districts of Orissa on October 29, 1999. But

NGOs reported that for five days after the cyclone, no special attention was

focussed on the needs of children. There was very little information on where

the children were, where they were going, or being taken.

How many children were actually displaced, how many died in the

earthquake that hit Gujarat on 26 January, 2000? No one has exact numbers. This

is true of all such situations of disaster or displacement. The need is to

ensure that along with immediate relief measures, proper information is

collected so that we can get a sense of the numbers affected, and ensure that

children are helped to move back to a semblance of normalcy as soon as possible.

This is to ensure that there are no long-term psychological implications. In the

absence of a holistic disaster mitigation policy, which is also designed to be

child friendly, this will not be possible. The same is true for rehabilitation

policies for development- related displacement.

Child participation: Many miles to go

It is only with the ratifying of the Child Rights Convention

that children's rights to participation began gaining formal recognition,

although several NGOs had initiated processes to enlist participation of

children and young adults long before the CRC. There is, however, no universal

or accepted definition of child participation. Various groups and individuals

have defined it according to their own understanding. There is still a fairly

long journey before this 'inclusion' of children's participation is internalised

and accepted widely.

Is the situation confronting the lives of our children bleak,

or is there reason for hope? Can we promise them an India that truly shines?

What do elections hold for these non-voters? Lest we forget, they are the adults

of tomorrow, and they willhold the adults of today accountable someday.

Enakshi Ganguly Thukral

Combat Law, Volume 3, Issue 1

April-May 2004

Combat Law, Volume 3, Issue 1

April-May 2004

Enakshi Ganguly Thukral works with HAQ: Centre for Child

Rights. HAQ is dedicated to the recognition , promotion and protection of all

children.

___________________________

The History of Child Rights in India

|

| © UNICEF/India/2007 |

| The right to play is a fundamental right of the child as enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. |

The Indian Constitution has a framework within which ample provisions exist for the protection, development and welfare of children. There are a wide range of laws that guarantee children their rights and entitlements as provided in the Constitution and in the UN Convention.

It was during the 50s decade that the UN Declaration of the Rights of the Child was adopted by the UN General Assembly. This Declaration was accepted by the Government of India.

As part of the various Five Year Plans, numerous programmes have been launched by the Government aimed at providing services to children in the areas of health, nutrition and education.

In 1974, the Government of India adopted a National Policy for Children, declaring the nation's children as `supremely important assets'.

This policy lays down recommendations for a comprehensive health programme, supplementary nutrition for mothers and children, nutrition education for mothers, free and compulsory education for all children up to the age of 14, non-formal preschool education, promotion of physical education and recreational activities, special consideration for the children of weaker sections of the population like the scheduled castes and the schedule tribes, prevention of exploitation of children and special facilities for children with handicaps.

The policy provided for a National Children's Board to act as a forum to plan, review and coordinate the various services directed toward children. The Board was first set up in 1974.

The Department of Women and Child Development was set up in the Ministry of Human Resource Development in 1985. The Department, besides ICDS, implements several other programmes, undertakes advocacy and inter-sectoral monitoring catering to the needs of women and children.

In pursuance of this, the Department formulated a National Plan of Action for Children in 1992. The Government of India ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child on 12 November 1992.

By ratifying the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Government is obligated "to review National and State legislation and bring it in line with provisions of the Convention".

The Convention revalidates the rights guaranteed to children by the Constitution of India, and is, therefore, a powerful weapon to combat forces that deny these rights.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development has the nodal responsibility of coordinating the implementation of the Convention. Since subjects covered under the Articles of the Convention fall within the purview of various departments/ ministries of the Government, the Inter-Ministerial Committee set up in the Ministry with representatives from the concerned sections monitor the implementation of the Convention.

At the provincial level

The State Governments have to assimilate - in letter and spirit - the articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child into their State Plans of Action for Children.

A number of schemes for the welfare and development of children have been strengthened and refined with a view to ensuring children their economic, political and social rights. The Convention has been translated into most of the regional languages for dissemination to the masses.

|

| © UNICEF/India/2007 |

| A young girl married as per elders wishes |

The mobilisation and greater involvement of NGOs in programmes for the development of children and women has increased the potential to accelerate the development process in achieving the national goals for children, as outlined in the National Plan of Action.

Accordingly, their involvement in dissemination of information of children's rights as well as in preparation of the Country Report was considered vital by the Government.

In order to facilitate an open consultative process, a three day National Consultation Workshop was held in Delhi during December 1994 on CRC. India's first country report drawing extensively from these discussions was enriched with constructive suggestions given by the experts for full implementation of the Rights of the Child.

Subsequently, eleven state level workshops were held around the country at Jaipur, Calcutta, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Pune, Jabalpur, Patna, Ahmedabad, Bhubaneswar and Chandigarh in the course of 1994 to disseminate the provisions and to give an opportunity to the states to highlight their issues and make suggestions.

Most of the rights detailed in the Convention are guaranteed in the Constitution of India. Since 1950, these rights have been expanded through the process of judicial interpretation and review.

The ratification of the Convention has made efforts more coordinated and sustained. The priority areas of action identified in each section of the country report present a long and serious agenda for government, its departments, NGOs and society in general.

The Convention has added legal and moral dimensions to child's rights and the obligation to fulfill children’s basic needs. Rights can be declared, policies can be formulated, but unless the life of the child in the family and community gets improved all efforts may be meaningless.

There is a need to raise awareness and create an ethos of respecting the rights of the child in Indian society. We need to empower the younger generation to assert their basic rights in order to realize their full potential.

India’s next CRC Report is to be submitted by 10 July, 2008. This will be the combined Third & Fourth Periodic report.

The government has formed a High-Level Committee for preparing the CRC Periodic Report. This has representatives from Central Govt. Ministries, including Ministry of External Affairs, State Governments and NGOs. UNICEF is also a member of this Committee.

Ensuring that child rights are met for every child is a daunting challenge for India but also a testimony to the Government’s commitment to the cause of children.

_________________________

Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Story and Stats

Tue, 04/17/2012 - 13:16 — LIG Reporter

2 years ago I missed the Howrah bound train somehow, and me and my sister had

to travel in a general bogie out of choice.

Indian Law: Corporal Punishment to be Banned

Tue, 07/27/2010 - 03:05 — LIG Reporter

The practice of corporal punishment is often adopted

by teachers, to implement discipline, among students. Corporal punishment is an

extreme breach of children’s right to protection, besides being a form of

physical/mental violence. As per Indian law, corporal punishment amounts to

human rights violations too. According to the official report of the Ministry of

Women and Child Development, conducted in 2007, on child abuse, two out of every

three students are physically abused. Further, 73% of boys face physical

punishment as compared to 65% of girls. All of this makes children fear

teachers and become miserable in class. However, most of the students

choose to suffer silently, rather than reporting the matter to parents or to

others.

Human Rights Violations: Child Abuse in Bangladesh

Sun, 07/18/2010 - 12:51 — LIG Reporter

Children in Bangladesh are often subjected to sexual abuse and bonded labor.

However, it is difficult to track down the exact number of such human rights

violations, due to several reasons. Firstly, Bangladesh has a low rate of birth

registrations. Sexual exploitation of children occur at all levels in the

country spanning brothels, homes, workplaces, hotels and even schools.

Human Rights Violations: Child Prostitution in India

Thu, 06/24/2010 - 19:28 — LIG Reporter

In India, it is a fact that young girls, irrespective of their socio-economic

backgrounds, are at a higher risk of being sexually exploited than boys. Several

surveys conducted way back in 1987, reported that 20 percent of women

prostitutes are actually minors.

Indian Law: Right of Children to Free Education

Wed, 06/23/2010 - 06:04 — LIG Reporter

In a developing country like India, a majority of the population is

illiterate and living far below the poverty line. Inevitably, the Right of

Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, was enforced by the Indian

government to regulate the education of children. Children related laws and

issues are of considerable interest to the government and the judiciary. Under

the Indian laws, every child is guaranteed, the right to admission, education

and the right to not be expelled from a school.

India Legal News: Central Government All Set To Amend The Juvenile Justice Law

Thu, 06/17/2010 - 15:59 — LIG Reporter

Children related laws and issues are multiplying day by day. Every time you

watch a news channel or read a newspaper that covers India legal news, there

will be a feature on children or issues relating to them. True, every child

needs care, nurturing, affection and education. These basic needs of a child

must be protected, even when a minor violates a law. The conventional norms in

India are such that it will not be possible for a child who is a suspect in any

case will be able to bounce back to normal life after going through legal

procedure in court. Be it in a family, school or in social life, the child will

be looked down upon like a criminal even if laws protect the child.

Indian Law for Juvenile Justice

Thu, 06/17/2010 - 15:49 — LIG Reporter

Many crimes are committed by children in India, so are crimes being done

against them. Children related laws and issues continue to pose serious concern

in different parts of the country. In the years 2003 - 2004, India witnessed a

rise of 7.9 percent in offences committed by minors. These offences include

arson, theft and cheating by minors who are in the age group of 16 to 18 years.

Indian law addresses the issue through the provisions of the Juvenile Justice

(Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000. The Act was enforced in April 2001

and replaced the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986. The Act has laid down a uniform

juvenile justice system throughout India.

Indian Laws: School Curriculum Suffers as Authorized Bodies Conflict

Wed, 06/09/2010 - 19:06 — LIG Reporter

Indian laws on education don’t impress today’s smart young students. The plan

of the government is to introduce a common curriculum for Class 12 Maths and

Science. This has met with opposition from the National Council of Educational

Research and Training (NCERT). Let’s not forget, the NCERT is the body

responsible for preparing school text books and curriculum. The push for a

common curriculum for maths and science, made by the Council of School Board of

Education (COBSE), is seen as a transgression of role by the council. A letter

by Prof G Ravindra, Director NCERT, to the CBSE president states that the COBSE

does not have the right to conduct the curriculum revision exercise, since

curriculum preparation and revision has been the right and forte of NCERT since

years.

Right to Education: Kerala Moves Ahead with New Initiatives

Wed, 06/09/2010 - 18:52 — LIG Reporter

Kerala, the land of lush backwaters and high literacy rate, figures in the

news, this time, for its ‘bold moves’ in the field of education. The state

boasts a literacy rate of 90.92 percent and a dropout rate of 0.83 percent.

Socially relevant, the next three stories reflect well on Kerala. One by one,

lets understand how the right to education is translated into initiatives by the

government of Kerala.

How to Identify Types of Guardians under Hindu Law

Tue, 06/08/2010 - 18:35 — LIG Reporter

The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, regulate the laws pertaining

to minority and guardianship among Hindus. It extends to whole of India except

for the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Few important definitions under the Act are:

_______________________

_______________________

Centre for Child and the Law:

While engaging with this legal instrument, the Centre for Child and the Law (CCL) found the CRC to substantially expand opportunities for governments and civil society actors to address the indignities perpetrated on children. The Centre also realized the need to deepen its own understanding of the way the CRC relates to Indian realities. It celebrated the progressive vision of this treaty, especially such as a child's right to autonomy, right to participation and the fact that it incorporates both civil and political rights as well as socio-economic cultural rights of the child. These have to be internalized by us as citizens and as a nation if we are to emerge as a society, which respects the human rights of children. CCL's organizational thrust is to establish these rights of the child within the Indian context, critique and go beyond these minimum standards where possible and actively engage with State and civil society actors to realize this radical vision.

The Centre advocates the need for a more accountable and responsive State. It argues against subsistence provisions for children in public policy and the quiet acceptance that budgetary constraints are grounds for the denial of the rights of children. It believes that a society that fails to address the root and structural causes of such violations and neglects to offer them the basic protections afforded in rights discourse, is a society that has got its priorities wrong. CCL also advocates for greater societal consciousness, to create a solidarity based peoples' movement to exert pressure from below. The underlying concern is to touch the lives of children and their families and communities, while strengthening the hands of those who strive to make child rights a reality.

Position:

Objectives:

While engaging with this legal instrument, the Centre for Child and the Law (CCL) found the CRC to substantially expand opportunities for governments and civil society actors to address the indignities perpetrated on children. The Centre also realized the need to deepen its own understanding of the way the CRC relates to Indian realities. It celebrated the progressive vision of this treaty, especially such as a child's right to autonomy, right to participation and the fact that it incorporates both civil and political rights as well as socio-economic cultural rights of the child. These have to be internalized by us as citizens and as a nation if we are to emerge as a society, which respects the human rights of children. CCL's organizational thrust is to establish these rights of the child within the Indian context, critique and go beyond these minimum standards where possible and actively engage with State and civil society actors to realize this radical vision.

The Centre advocates the need for a more accountable and responsive State. It argues against subsistence provisions for children in public policy and the quiet acceptance that budgetary constraints are grounds for the denial of the rights of children. It believes that a society that fails to address the root and structural causes of such violations and neglects to offer them the basic protections afforded in rights discourse, is a society that has got its priorities wrong. CCL also advocates for greater societal consciousness, to create a solidarity based peoples' movement to exert pressure from below. The underlying concern is to touch the lives of children and their families and communities, while strengthening the hands of those who strive to make child rights a reality.

History:

The Centre for Child and the Law (CCL) was established on 1

April 1996 , in the National Law School of India University (NLSIU), Bangalore .

The idea to start a Centre was to further the vision of NLSIU to marry legal

expertise with the social sciences, and was a spin off from the preliminary work

undertaken in collaboration with UNICEF. It stemmed from a deep interest to

place issues of the child at the forefront of public policy. Shortly after, in

July 1999, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India,

conferred the Juvenile Justice Chair on NLSIU, which is occupied by Prof. Babu

Mathew the then Faculty Co-ordinator, who has played a significant role in

developing the Centre. This, along with the fact that CCL is located in a

premier and autonomous Law University, has provided it with the opportunity to

play a more strategic role in the arena of law and social change.

Despite the Centre being an extension programme of NLSIU, it has to mobilize its own resources. Initial grants and seed monies from funding agencies such as UNICEF and National Foundation for India (NFI) lent the necessary stability CCL required in the early years. To meet its infrastructural requirements, Child Relief and You (CRY) stepped in to fund the vibrant office space located on the first floor of the NLSIU building, where the Centre now operates from.

Since December 1999, having received funds from the Humanistic Institute for Co-operation with Developing Countries (HIVOS), the Centre was able to broaden its scope of work. HIVOS continues to actively support the work of CCL.

The Centre's core funding now (October 2010 to September 2012) comes from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust(SDTT), while small short term projcts are being funded by the Karnataka State Legal Services Authority and National University of Education Planning and Administration(NUEPA).

Mission:Despite the Centre being an extension programme of NLSIU, it has to mobilize its own resources. Initial grants and seed monies from funding agencies such as UNICEF and National Foundation for India (NFI) lent the necessary stability CCL required in the early years. To meet its infrastructural requirements, Child Relief and You (CRY) stepped in to fund the vibrant office space located on the first floor of the NLSIU building, where the Centre now operates from.

Since December 1999, having received funds from the Humanistic Institute for Co-operation with Developing Countries (HIVOS), the Centre was able to broaden its scope of work. HIVOS continues to actively support the work of CCL.

The Centre's core funding now (October 2010 to September 2012) comes from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust(SDTT), while small short term projcts are being funded by the Karnataka State Legal Services Authority and National University of Education Planning and Administration(NUEPA).

To institutionalize a child rights culture in our society that

will enable children to live with dignity and respect.

Position:

CCL believes that the State has a duty to meet the needs of

every Indian child, with priority given to the most marginalized. However, as an

actor of civil society CCL feels it has a responsibility to supplement efforts

made by the State to safeguard the interest of children and work in

constructive, critical collaboration with the state and civil society towards

realizing this common goal.

Objectives:

While building the Center the aim was to develop a space where

research focuses on building linkages between the globalization process and the

violation of child rights and which can enable the development of a South based

jurisprudence which centers around the use of education as a strategy to combat

the exploitation of children. The Center aimed at critically examining the law

and policies and monitoring their implementation as well. Capacity building with

a child rights perspective of various stakeholders including government

functionaries involved with either the implementation or monitoring of laws

related to children, has been one of the core activity of CCL.

-

To deepen perspective and promote capacity building on child rights and to integrate modules on child rights in the curricula of various professional courses.

-

To facilitate the full implementation of the UN CRC

-

To contribute to the development of a comprehensive legal framework for children through a Child Code that will also influence system and law reform

-

To contribute to efforts aimed at lobbying for effective monitoring mechanisms such as the Children's Commission

-

To evolve and support effective service delivery and response systems for children, their families and communities

-

To bridge the gaps and promote solidarity partnerships between disciplines, academia, local communities ,social movements and civil society at large for mutual benefit and aimed at the best interests of children.

-

To serve as a resource pool on child related issues

-

To help shape, institutionalize and prioritize a human rights agenda for children at various levels and arena

-

To lobby with state and civil society to enable realization of child rights provided for under progressive laws in India

-

To empower and enable increased assertion from child rights holders for claiming their basic rights

-

To contribute to policy, law and practice that will enable compliance with the Constitution, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and other normative frameworks.

-

To integrate Teaching, Research and Field Action on child rights within NLSIU, to impact the discourse on child rights, the legal education at NLSIU and contribute to the development of a cadre of trained child rights professionals

-

To build replicable demonstration projects that will impact policy, law and practice on child rights

-

To strengthen the capacities of state governments to establish and implement the provisions of Commission of Protection of Child Rights Act by providing socio-legal research support and facilitation of inter-state consultation.

-

To understand the role of various human rights institutions (as well as quasi-judicial bodies such as the Child Welfare Committees under the JJ Act) in relation to such institutions), in ensuring justice to the child

-

To foster dialogue and explore mechanisms for complementary work among various independent human rights institutions and quasi-judicial bodies in India

Methodology /Strategies:

The Center has always been guided by a keen desire to

understand the social reality in which deprived children of India are placed. It

is important to note that all the areas in which the CCL is engaged primarily

concerns children of families who belong to the socially and economically

disadvantaged classes and caste groupings in India.

- Evidence based research: Identifying and highlighting gaps in child-related data and service delivery systems and developing a database

People's participation in reform through Participatory

Action Research: Critically examining existing laws and policies for

children, facilitating participatory consultative processes with relevant

stakeholders and actors including children and making recommendations for reform

This has been translated into action primarily through direct involvement in

various ongoing interventions through our association with NGOs, Social

Activists, Social Movements and Administrators ranging from the Secretary to the

concerned department to school teachers in government institutions.

Links with Government bodies: - Strengthening law as a tool for social change: Developing and proposing new laws and nuanced protocols to address the lacunae in current law and practice.

- The University as a space for dialogue, debate and facilitating collective response to issues concerning the child: A special dimension of the CCL’ strategy, since it is located in an academic environ, is effectively utilizing the platform of being located within a University to initiate debate, build partnerships and influence law, policy and practice in favour of children. CCL has also engaged itself with academic programmes and courses and of late efforts have been further accelerated in this direction.

As a Center, we believe in working in collaboration with all

those working on the issues of marginalization, so as to contribute towards

strengthening platforms committed to Child Rights. This is in pursuance of our

string commitment to assist in bridging the gap between theory and practice, law

and social reality, NGO – Government – Academia. In this regard we are

constantly enhancing our networking with various Government and Non Governmental

Organizations and moving towards forging links with new partners – both within

the State and elsewhere.

Links with Government bodies:

1. Department of Woman and Child Development, Government of

Karnataka, Bangalore

2. Department of Primary and Secondary Education, Government of Karnataka, Bangalore

3. Department of Labour, Government Of Karnataka, Bangalore

4. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, New Delhi

5. Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Women and Child Development, Government of India, New Delhi

6. Department of Elementary Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, New Delhi

Quasi Government Institutions:2. Department of Primary and Secondary Education, Government of Karnataka, Bangalore

3. Department of Labour, Government Of Karnataka, Bangalore

4. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, New Delhi

5. Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Women and Child Development, Government of India, New Delhi

6. Department of Elementary Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, New Delhi

- National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) – Bangalore

- National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development (NIPCCD)

- National Child Labour Institute – New Delhi

Juvenile Justice National Desk: www.jjindia.net

Playing a leadership role in the Juvenile Justice National

Desk(Ms. Arlene Manoharan is a member of this network). It is an emerging

national network on the issue that aims to build a national level community of

practice that can directly impact the lives of children at the micro level as

well as law and policy at the national level.

World Social Forum (WSF) and Karnataka Social Forum (KSF):

National-State Some of our staff have been active members of this forum that

contributes immensely to the broadening of our vision and strategies in our work

with children.

People’s Campaign for Common School System (PCCSS): National

and State Level –CCL has been the founder member of the campaign and on the

National Executive Committee.

Campaign Against Child Labour (CACL): National and State Level

– CCL has been an active member in this campaign and is also on the legal

support and Core Committee Member of the campaign.

Campaign Against Child Trafficking (CACT): State Level – CCL

has been an active member in this campaign and providing legal support and part

of advocacy, advocacy and networking committee of the campaign

National Alliance of People’s Movement: Some of our staff have

been active members of this alliance which contributes immensely to the

broadening of our vision and strategies in our work with children.

Jeevika : This is a movement against bonded labour and bonded

child labour in Karnataka. CCL has been involved in providing support to the

research processes presently underway and in facilitating the involvement of the

State Government in responding to the issues raised in the process.

Campaign Against Female Foeticide : This Campaign is being

driven by Society for Integrated Rural Development, Tamilnadu. CCL also played

pivotal role in bringing together experts, academia and activists together to

discuss the issue of sex selective abortions and female foeticide.

National Alliance for Fundamental Right to Education (NAFRE) :

CCL, NLSIU is the founding partners of this network and has since played a major

role in taking the campaign forward.

Bangalore forum for Street and Working Children : It is a local

forum consisting fo around 15 member organizations working directly with street

and working children in Bangalore.

Tamilnadu NGO Forum for Street and Working Children : CC

actively supports this state level forum having a membership of more than 40

organizations.

National NGO Forum for Street and Working Children : This is a

national network of NGos working for street and working children.

Child Line : This is a project supported by the Ministry of

Social Justice and Empowerment consisting of a network of organizations

implementing and supporting the 24 hour Hotline service for children. Various

Centers have been set up in different cities around the country.

NGO's:

Over the period, CCL has buildup a good working relationship

with a number of NGOs and activists in the field both at the local and national

levels. In Bangalore, especially a group of persons representing the State

Government Department for Woman and Child Development, activists from NGOs

working on issues of children in various difficult circumstances, experts from

NIMHANS and others have been brought together to share in a process of dialogue

on Law and Policy Reform specially with regard to the Juvenile Justice Act. This

Platform has created the foundation for ongoing debate and partnership between

children. Likewise, contacts have been made and developed with the NGOs working

in the areas of education and child labour.

Links with International Institutions/ organizations

TheCentre for Child and the Law(CCL) has also been able to develop link with the South African Law Commission (SALC). CCL facilitated a rich and meaningful dialogue with the members of SALC along with UNICEF. This discussion centered around the issue of Law and Policy for children and the efforts made by both the countries in undertaking research, initiating dialogue and moving towards meeting international standards. This positive interaction created the foundation for partnership with CCL and SALC.

CCL is completing a decade of its existence in the National Law School of India University and has made a sound platform by establishing ourselves as a local and national resource base on issues related to child labour, education, and juvenile justice. We also need to be able to offer our expertise on all other areas related to children and we cognize that this demands a lot more work.

Studies:Links with International Institutions/ organizations

TheCentre for Child and the Law(CCL) has also been able to develop link with the South African Law Commission (SALC). CCL facilitated a rich and meaningful dialogue with the members of SALC along with UNICEF. This discussion centered around the issue of Law and Policy for children and the efforts made by both the countries in undertaking research, initiating dialogue and moving towards meeting international standards. This positive interaction created the foundation for partnership with CCL and SALC.

CCL is completing a decade of its existence in the National Law School of India University and has made a sound platform by establishing ourselves as a local and national resource base on issues related to child labour, education, and juvenile justice. We also need to be able to offer our expertise on all other areas related to children and we cognize that this demands a lot more work.

- Children as victims of armed conflict in Manipur

- Study and initial work on children and communalism in Gujarat

- Tibetan Refugee children

- Disability and Juvenile Justice (ongoing)

- Study of Contract Labour System in Karnataka

PUBLICATIONS

-

The Karnataka Gram Panchayat’s (School Development and Monitoring Committees)-Model Bye -Laws (CCL-2006)

-

Report of A Study to Evaluate the Functioning of School Development and Monitoring Committees in Karnataka (CCL in collaboration with GoK and APF, 2005)

-

Report of the Study Group on Contract Labour System in Karnataka; Report submitted to Ministry of Labour, Government of Karnataka (CLS, 2004)

-

Universalisation of School Education: The Road Ahead (CCL, 2004)

-

Reflections on the life and working conditions of the Pourakarmikas in Bangalore; Report of the Round Table Group on Law, Poverty and Marginalization (Law & Society Cluster, NLSIU 2002)

-

Juvenile Justice (Care & Protection of Children) Act, 2000; A Critique (CCL, 2002)

-

Female Infanticide and Foeticide - A Legal Perspective (CCL,1999)

-

Report on the National Consultation on Medico-Legal Issues related to Female Foeticide (CCL,1999)

-

Report on the National Consultation on Juvenile Justice (CCL,1999)

-

Report on the National Consultation on Right to Education: A Strategy to Eliminate Child Labour (CCL, 1998)

-

Kannada Documents

________________________________________

Laws

&

Policies

While all children have equal rights, their

situations are not uniform. At the same time, childhood and the range of

children’s needs and rights are one whole, and must be addressed holistically. A

life-cycle approach must be maintained. Keeping this in mind, there are several

national laws and policies that address the different age-groups and categories

of children.

1890: Guardians and Wards Act

1948: Factories Act (Amended in 1949, 1950 and 1954)

1956: Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act

1956: Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act (amended in 1986)

1956: Probation of Offenders Act

1960: Orphanages and Other Charitable Homes (Supervision and Control) Act

1974: National Policy for Children

1976: Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act

1986: Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act

1987: Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act

1989: Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act

1992: Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles and Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act

1994: Transplantation of Human Organ Act

1996: Persons with Disabilities (Equal Protection of Rights and Full articipation) Act

2000: Information Technology Act

2000: Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act (2000)

2000: The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act

2002: The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act

2006: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act

2006: Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act (Amendment, 2006)

2009: The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009

1890: Guardians and Wards Act

1948: Factories Act (Amended in 1949, 1950 and 1954)

1956: Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act

1956: Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act (amended in 1986)

1956: Probation of Offenders Act

1960: Orphanages and Other Charitable Homes (Supervision and Control) Act

1974: National Policy for Children

1976: Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act

1986: Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act

1987: Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act

1989: Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act

1992: Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles and Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act

1994: Transplantation of Human Organ Act

1996: Persons with Disabilities (Equal Protection of Rights and Full articipation) Act

2000: Information Technology Act

2000: Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act (2000)

2000: The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act

2002: The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act

2006: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act

2006: Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act (Amendment, 2006)

2009: The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009

_______________________________

Children

| International Legal Instruments | Status of Ratification/Signature/Adoption |

|---|---|

| Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 | RATIFIED on 11 December 1992 with a declaration on Article 32 |

| Optional Protocol to CRC on Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography | SIGNED on 15 November 2004 and RATIFIED on 16 August 2005 |

| Optional Protocol to CRC on involvement of Children in Armed Conflict | SIGNED on 15 November 2004 and RATIFIED on 30 November 2005 |

| Amendment to article 43 (2) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1995 | NOT SIGNED |

| Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages, 1962 |

___________________________________________

The age of majority for children in England and Wales varies; there are many age related rules that distinguish between children of different ages for different purposes. The age of majority typically ranges from between sixteen years of age (in which school no longer becomes mandatory) to eighteen years of age (for voting rights and the consumption of alcohol).

Children’s rights are provided by a large number of laws – some that specifically were enacted to protect children, and others that contain just a few sections that pertain to children but provide them with essential rights. There are numerous pieces of legislation that provide children with rights in the areas of education, medicine, employment and the justice system. Given the volume and complexity of these laws, this report provides a necessarily broad overview of the substantive pieces of legislation as they affect children’s rights in these areas.

The government has recently introduced a National Service Framework, which provides that healthcare services for children should be designed and delivered around the particular needs of children.[24] The framework intends “to lead to a cultural shift, resulting in services being designed and delivered around the needs of children and families.”[25]

It is the duty of the Secretary of State to provide children with education in England and Wales, and this duty is typically performed by Local Education Authorities (LEA) for each county in England.[43] Education in Wales is a devolved area, meaning that it can pass regulations to address educational issues separately from England. Regulations specifically relating to Wales are not addressed in this report.

Discrimination in its various forms (race,[57] gender,[58] disability,[59] and sexual orientation[60] or religion[61] in the higher and further education sectors) is prohibited when providing education in England and Wales. LEAs have a duty to identify children with special needs and to then make an assessment of what needs they have and then to make a statement of these special needs, to include details of the assessment and the special educational provisions that are to be made to meet these needs. The statement includes the type of school or institution the LEA considers to be appropriate for the child, or to specify the name of the mainstream public school that it considers appropriate for the child, and any special educational provisions that it considers necessary.[62] It is currently general policy to include special needs children into mainstream public schools unless this is incompatible with the wishes of the parents or would have a negative impact on the efficient education of other children.[63] If the statement of special needs names a public school, that child must be admitted to that school.[64]

There are a number of laws that prohibit the use and exploitation of children in dangerous labor. The following examples are extracted from a House of Commons Library Standard note and include:

The Sexual Offences Act 2003 is currently the substantive piece of legislation regarding sexual offenses and introduced the specific offense of trafficking individuals into, within or out of the England and Wales for the purposes of sexual exploitation. The wording of the trafficking offence does not mirror that in the UN Protocol to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking. During debates on the offense, Parliament noted that it was specifically not worded in this manner because Parliament “did not wish to limit the offences to those carried out by the use of threats, force, coercion, abduction, fraud, deception or abuse of power or vulnerability ... Its view was that where these abusive elements were present they could be charged in their own right.”[84]

A person commits an offense of trafficking an individual for sexual exploitation under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 if he or she intentionally arranges or facilitates the arrival in, movement within or out of the UK, and intends to do an act, or believes that another person is likely to do an act, in respect to the person that he or she has trafficked in or out of England and Wales that, if performed, involves the commission of a “relevant offence.”[85] The offense of trafficking covers situations where a person is brought through England and Wales as an interim destination and also covers situations where a person would be guilty of the offense, for example through arranging travel documents, even if the person being trafficked is ultimately not sexually exploited. The trafficking offenses all have extra-territorial application, making it possible to prosecute any British person that conducts the trafficking activity specified in the Act in any country in the world without the need for an equivalent offense in that country.[86] The maximum penalty for trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation is fourteen years imprisonment.

Trafficking to generally exploit people is also covered under the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc.) Act 2004. This Act provides that it is an offense for a person to arrange travel for someone into, within or out of the United Kingdom with the intention that he or she will exploit that person, or a belief that another person is likely to exploit them. A person is exploited if he or she is forced into labor or slavery; encouraged, required or expected to perform acts regarding the unlawful removal of human organs; has been subjected to force, threats, or deception designed to induce him or her to provide services of any kind or provide another person or enable another person to acquire benefits of any kind, is requested or induced to undertake any activity, having been chosen as the subject of the request or inducement on the grounds that he is young and an older person would be likely to refuse the request or resist the inducement.[87] These sections also apply to acts done outside England and Wales by British nationals, subjects, and citizens.[88] A person found guilty of an offense under this Act may be imprisoned for up to fourteen years.

The statutory framework for the basic protection of children once in England and Wales is provided for through the Children Act 1989 and the Children Act 2004. The Children Act 1989 places a duty on local authorities to prevent children in their area from suffering ill treatment or neglect by ensuring services are provided for them[89] and to investigate any situation where a child in their area is subject to an emergency protection order; is in police protection; or if there is reasonable cause to suspect that the child is suffering or likely to suffer from significant harm.[90] An example of services provided to children that have suffered from ill treatment or neglect is that of safe houses provided by West Sussex County Council, the local authority covering the area surrounding Gatwick Airport.[91]

The Children Acts provide Local Authorities with the power to apply to the court for an emergency protection order if there are reasonable grounds to believe that the child will suffer from significant harm if he or she is not removed to accommodation provided by the local authority; that the local authority are making enquiries that are being frustrated by access to the child being refused; or if inquiries are being made and frustrated through access to the child being unreasonably refused and there is reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering or likely to suffer significant harm.[92] Emergency protection orders can be granted by the courts for up to eight days and has the effect of giving the local authority the power to remove the child from the home or prevent the child from being removed from a hospital or state accommodation; it also gives the Local Authority limited parental responsibility for the child.[93]

Children arrested for crimes in England and Wales and held in custody must be separated from the adult population of the jail. Their guardians must be notified as soon as reasonably practicable and informed of the charges brought against the child and the child’s place of detention.[96] During any court proceedings involving the child under the age of sixteen the law requires the attendance of the child’s guardian during all proceedings, unless this is unreasonable in the circumstances of the case.[97] The general principle for children charged with crimes is that they should not be held in police custody but instead taken care of by social services in Local Authority accommodations. The principle is considered to be of such importance that police custody officers have a statutory duty to release juveniles to local authority accommodations unless they can certify that specific circumstances make it impracticable for this to occur, or for children aged twelve or over no secure accommodation is available, and no other local authority accommodation is adequate to protect the public from the serious harm posed by the child.[98]

The principal aim of the juvenile justice system is to “prevent offending by children and young people.”[99] To achieve this aim, the juvenile justice system in England and Wales progresses through a series of steps.[100] The first two, which apply only to less serious crimes, aim at preventing the child from entering the juvenile justice system through a series of behavioral contracts and other methods designed to correct the child’s behavior to prevent him or her from re-offending or committing a serious offense.[101] For example, a system of cautioning has been developed for young offenders through reprimands and warnings that are given to those who admit guilt to the police for their crimes and for whom there is sufficient evidence that any prosecution for the offence would be successful.[102] Upon receiving the reprimand or warning the young offender is then referred to the Youth Justice Board who arranges for the youth’s participation in a rehabilitation programme.

For children to whom these preventive methods do not apply, for example, due to the seriousness of the offense, or who have exhausted them, the juvenile justice system then operates in the form of a Youth Court, which hears cases of ten to eighteen year olds.[103] This youth court was established to prevent children and young people from entering into contact or associating with adult suspects during any phase of a trial.[104] The public are excluded from these courts; further, reporting restrictions may be placed on what the media may publish from these proceedings. There are also laws that protect the anonymity of children appearing before the court.[105] The Youth Court is a specialized magistrates’ court that is comprised of justices of the peace, with three normally present for each case.[106] The court has a range of different sentences for young offenders;[107] for example, supervision orders[108] that can have a variety of conditions attached to them or an Action Plan Order, an intensive, three month long community-based programme.[109] More serious custodial methods of punishment are detention and training orders.[110] These orders are normally given to children representing a “high level of risk [to the public], have a significant offending history or are persistent offenders and where no other sentence will manage their risks effectively.”[111] They apply for a minimum period of four months to a maximum period of two years, with half of the sentence being served in custody and the remainder in the community supervised by a “youth offending” team.[112] Only those offenders over the age of fifteen may be sentenced to detention in a young offenders’ institution, although this latter restriction does not apply to children aged ten and over convicted of murder.[113]

For very serious offenses, children are prosecuted in the Crown Court. A practice direction issued by the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales in respect to Crown Court prosecutions of children requires that the “trial process should not itself expose the young defendant to avoidable intimidation, humiliation or distress. All possible steps should be taken to assist the young defendant to understand and participate in the proceedings. The ordinary trial process should so far as necessary be adapted to meet those ends.”[114] The Children and Young Persons Act 1933 requires that the welfare of the defendant should be regarded during any criminal proceedings,[115] and the practice direction requires that breaks be frequently taken, that the formal court attire of robes and wigs not be worn, and that there be no recognizable police presence in court without good cause.[116] The Crown Court is the only court that is permitted to follow these rules for sentencing children between ten and eighteen years old that have committed an offense that is punishable by fourteen or more years’ imprisonment for adult offenders, children that have committed murder, or certain sexual offenses, may be sentenced for up to the adult maximum for the same offense.[117] The young offenders are not placed in prisons alongside adults, but can be placed in secure training centers, secure children’s homes, or young offenders’ institutions.[118]

Children’s Rights: United Kingdom (England and Wales)

Executive Summary

This report provides a basic overview of the laws regarding children’s rights in a number of fields. The United Kingdom has a large number of laws protecting children and guaranteeing them basic rights – both for areas in which there is now an ‘entitlement’ such as education, as well as in areas in which they need rights to ensure protection, such as in the criminal justice system. Given the number and complexity of these laws this report provides a broad overview of legislation and common law as it applies to children’s rights in England and Wales only. (PDF, 180KB)Introduction

Within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, England and Wales is the component nation in which largely English law prevails. This report does not address children’s rights in Scotland or Northern Ireland, although a number of the provisions discussed in the paper may also apply to them. The common law in England and Wales provides that the responsibility for the care and protection of children is with their parents “as guardians by the law of nature, and on the Crown as parens patriae,”[1] with the powers of a child’s parents somewhat limited in certain areas by law. There are a number of substantive pieces of legislation affecting children and their rights in a number of different areas. The most substantive piece affecting children and their basic rights to a secure and safe environment is the Children Act 1989. This Act introduces the term ‘parental responsibility’ rather than the common law concept of custody. Parental responsibility is defined as “all the rights, duties, powers, responsibilities and authority which by law a parent has in relation to the child and his property.”[2]The age of majority for children in England and Wales varies; there are many age related rules that distinguish between children of different ages for different purposes. The age of majority typically ranges from between sixteen years of age (in which school no longer becomes mandatory) to eighteen years of age (for voting rights and the consumption of alcohol).

Children’s rights are provided by a large number of laws – some that specifically were enacted to protect children, and others that contain just a few sections that pertain to children but provide them with essential rights. There are numerous pieces of legislation that provide children with rights in the areas of education, medicine, employment and the justice system. Given the volume and complexity of these laws, this report provides a necessarily broad overview of the substantive pieces of legislation as they affect children’s rights in these areas.

Implementation of International Rights of the Child

The United Kingdom is party to numerous treaties regarding the rights of children, notably the- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified 12/16/1991;[3]

- United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child, ratified 1/15/1992;[6]

- European Convention on the Adoption of Children, ratified 12/21/1967, entered into force 4/26/1968;[7]

- European Convention on the Legal Status of Children born out of Wedlock, ratified 2/24/1981, entered into force 5/25/1981;[8]

- Convention Against Discrimination in Education, accepted by the UK 3/14/1962;[9]

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, acceded to 2/24/1967;[10]

- Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, ratified 10/20/1986;[11]

- Hague Convention on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law, Recognition, Enforcement and Co-operation in Respect of Parental Responsibility and Measures for the Protection of Children, signed 1/4/2003;[12]

- Hague Convention on the Protection of Children in Intercountry Adoption, ratified 2/27/2003;[13]

- European Convention on the Adoption of Children, ratified 12/21/1967;[14]

- Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages, acceded to 7/9/1970;[15]

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified 5/20/1976;[16]

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, ratified 4/8/1976;[17]

- The European Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Concerning the Custody of Children, ratified 4/21/1986;[18]

- Minimum Age Convention, ratified 7/6/2000;[19]

- Convention concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour, ratified 3/22/2000;[20]

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights;[21] and the

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, ratified 5/20/1976.[22]

Child Health and Social Welfare

General Access to Healthcare

The United Kingdom does not have a written constitution that provides any guarantees regarding access to healthcare. It does, however, have a comprehensive national health service founded on the principle of providing treatment according to clinical need rather than the ability to pay. The Secretary of State has a number of statutory responsibilities under the National Health Service Act 1977 to ensure that, where possible, a free and comprehensive health service is provided in England and Wales to improve both the physical and mental health of the people of the country and to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses.[23]The government has recently introduced a National Service Framework, which provides that healthcare services for children should be designed and delivered around the particular needs of children.[24] The framework intends “to lead to a cultural shift, resulting in services being designed and delivered around the needs of children and families.”[25]

Prenatal and Postnatal Care

Healthcare facilities are free and available for British children and infants, and the rate of infant mortality is relatively low, with 3,368 infant deaths (under one year of age) registered in England and Wales in 2006, at a rate of five per 1,000 live births.[26] The National Service Framework regarding pre- and postnatal care of infants has been welcomed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The policy aims to provide mothers with a choice of either a midwife or a doctor for prenatal care; a choice of place of birth between a home birth, midwife centre birth, or a hospital birth with a doctor or a midwife. These services are provided at no additional charge through the National Health Service.Healthcare: Children and Consent

Under the Children Act 1989, the term parental responsibility is defined to include the parents’ right to consent to medical treatment.[27] An individual that does not have parental responsibility for the child, but has them in his or her care, for example a doctor or a teacher, “may do what is reasonable in all the circumstances of the case for the purpose of safeguarding or promoting the child’s welfare … though it will presumably only be reasonable to act without first obtaining the consent of the child’s parents … in an emergency or if the treatment is trivial.”[28] When children reach the age of sixteen, provided they are mentally competent, they are considered to be sui juris and capable of consenting to treatment themselves.[29] Prior to this age, however, a child that has achieved a sufficient degree of understanding and intelligence regarding any treatment that he or she is about to undergo may be considered competent and capable of providing valid consent to this treatment. This level of competence varies according to the seriousness of treatment and “reflects the staged development of a normal child and the progressive transition of the adolescent from childhood to adulthood.”[30] This concept is known as "Gillick competence," [31] and may be overruled by a parent if the child is refusing to consent to treatment; a parent, however, cannot overrule a Gillick competent child’s consent to treatment.[32]Education